An Eclipse Expedition to Oregon

Every month, during new moon, the Moon passes between the Earth and the Sun. Unfortunately, due to the Moon’s tilted orbit, it usually passes just above or below the Sun, making those of us here on Earth oblivious to its passage. Twice a year though, the Moon passes through the plane of our orbit around the Sun during new moon, leading to a solar eclipse. Some of these eclipses are partial, where the Moon takes a bite out of the Sun, typically unbeknownst to those not monitoring the skies with eclipse glasses. More spectacular are the total eclipses, which occur when the Moon is close enough to us in its elliptical orbit that its disk is large enough to fully obscure the Sun, turning day briefly into dusk. A third option occurs when the Moon is farther away from us in its elliptical orbit. Even if the geometry is correct to produce a total eclipse, the Moon’s smaller size in this case means its not large enough to fully cover the Sun. This results in an annular eclipse, in which a ring (or “annulus”) of sunlight is visible around the dark circle of the new moon.

Partial eclipses are a dime a dozen, but given the small size of the Moon’s shadow relative to Earth, total and annular eclipses can only been seen from a narrow strip of land. Stand even a few meters outside that band, and you’ll see just a partial eclipse. I’ve seen probably half a dozen partial eclipses over the years, and in 2017, we made the eight hour drive from southern Utah to Riverton, WY to see a total solar eclipse. (The drive ended up being twice as long on the return, due to “eclipse traffic.”) That experience was spectacular, and immediately led to conversations about when we could see another.

While annular eclipses don’t provide quite the all-encompassing sensory experience of a total eclipse, I was nevertheless excited to complete my own personal “eclipse trifecta” by travelling to Oregon last weekend for the October 14, 2023 annular eclipse. The last annular eclipse visible from the United States was over a decade ago, on May 20, 2012, when the path of annularity swept across the American Southwest. That date just happened to correspond with my undergraduate commencement ceremony, which was sadly not in the path of annularity. This prompted me to inquire with school officials about whether attendance was required to receive my degree. I was told it was, and thus that eclipse expedition ended before it began.

The 10/14/23 eclipse had been circled on my calendar for a long time, especially since we moved to Washington in 2019 and would be just a few hours north of the path of annularity. I had grand plans of leading a field trip for my students, but a national shortage of 12-passenger vans thwarted that idea months ago. Instead, on the evening of October 13th, my wife and I made the 4.5 hour drive from central Washington to La Pine State Park in Oregon, just inside the annular eclipse track. The weather forecast had been looking poor for the past week, and the last hour of the drive was through a steady rain. However, forecasts for the eclipse morning had slightly improved over the past 24 hours, and it seemed there would be at least a chance for some clearing around eclipse time. The campground was full, which I’m guessing was out of the ordinary for a wet, cold, weekend in mid-October.

The morning of the eclipse dawned cold and mostly cloudy, though there were patches of blue sky visible here and there. We decided to head southeast, away from the Cascades, to improve our chances of clear skies. After about an hour of driving, through intermittent patches of eclipse traffic, we arrived on the rim of “Hole-in-the-Ground,” a ~1 mile wide volcanic crater known as a marr, formed when magma encountered shallow groundwater about 15,000 years ago, resulting in a large explosion. Several dozen other groups were camped out on the rim of the hole in the hopes of seeing the eclipse. We pulled off into the sage with about half an hour to go until the start of the annular eclipse. The skies looked grim, with the patches of blue from an hour earlier having given way to a nearly uniform layer of gray mid-level clouds. We briefly debated weather to high-tail it east toward an area of sunlight on the horizon an unknown distance away, but eventually decided we probably wouldn’t make it in time.

This turned out to be the right call. About 15 minutes before annularity began, a hole in the clouds began to materialize and we caught our first glimpse of the partially eclipsed Sun:

With the Sun nearly 90% eclipsed at this point, the light began to take on a noticeably unnatural tone, much as it did in the final minutes before the total eclipse in 2017. The gap in the clouds became steadily larger, as did our excitement at the prospect we might actually see the celestial alignment we had come for. At 9:20 am, annularity began, right on schedule, as the Sun peered down through the only sizeable break in the clouds for miles around. Joyous shouts of excitement echoed across the hole as other parties spotted the hole-in-the-sun through the hole-in the-clouds from the hole-in the-ground. What cosmic symmetry!

The extra hour of driving had bought us an additional minute or so of annularity, for a total of just under four minutes. That time flew by. By the time we looked through the telescope a few times and snapped a few pics, the annular eclipse was over. The clouds sealed back up again about 10 minutes after annularity ended.

Having seen what we came to see, it was now 10:00 am on a beautiful (if you’re not trying to see an eclipse) and pleasant weekend in central Oregon. We spent the rest of the weekend going on some short hikes and enjoying some great food in Bend before returning home.

From A(storia) to B(rookings) Down the Oregon Coast

As another summer comes to a close, I am enjoying looking back at some photos from the past few months. In mid-August we had the chance to spend two weeks in Oregon, most of which we spent along the spectacular Oregon Coast. While not my first trip to the coast, this was my first time visiting some of the more remote southern sections of the coast, and over the course of the two weeks we were actually able to drive the entire Oregon section of Highway 101, all the way from Washington to California.

We began the trip in Astoria, gazing at the mouth of the Columbia River in Fort Stevens State Park and visiting the site of Fort Clatsop, quarters for the Lewis & Clark Expedition during the winter of 1805-1806. From there we travelled south to visit with friends in Rockaway Beach for several nights before continuing on to Newport and then heading inland for other adventures. A few days later we returned to the coast at the mouth of the Rogue River in Gold Beach, just 45 minutes or so north of the California border. After a quick drive into the Golden State, we began moving north, through Coos Bay, Bandon, Florence, and the Oregon Dunes before returning to Newport. After a final few days in the Lincoln City area, it was back up the Columbia River Gorge to Washington and back to work! Here are some of my favorite images from the trip, arranged from north to south:

Late afternoon light on the beach in Rockaway Beach, Oregon. The northern third of the Oregon Coast is characterized by long stretches of wide, sandy beach. Sand is relatively abundant here thanks to the Columbia River, though the supply has been greatly diminished since dams started popping up on the Columbia beginning in the mid 1900s.

I had been hoping to do some night sky photography from the beach, but despite relatively benign daytime weather, most nights looked something like this, with dense mist and fog enveloping the shore. Here, lights from Rockaway Beach illuminate the fog.

Sunset from Rockaway Beach, Oregon.

Sunset from Rockaway Beach, Oregon.

Brown pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis) and Pacific harbor seals (Phoca vitulina) on Salishan Spit near Lincoln City, Oregon.

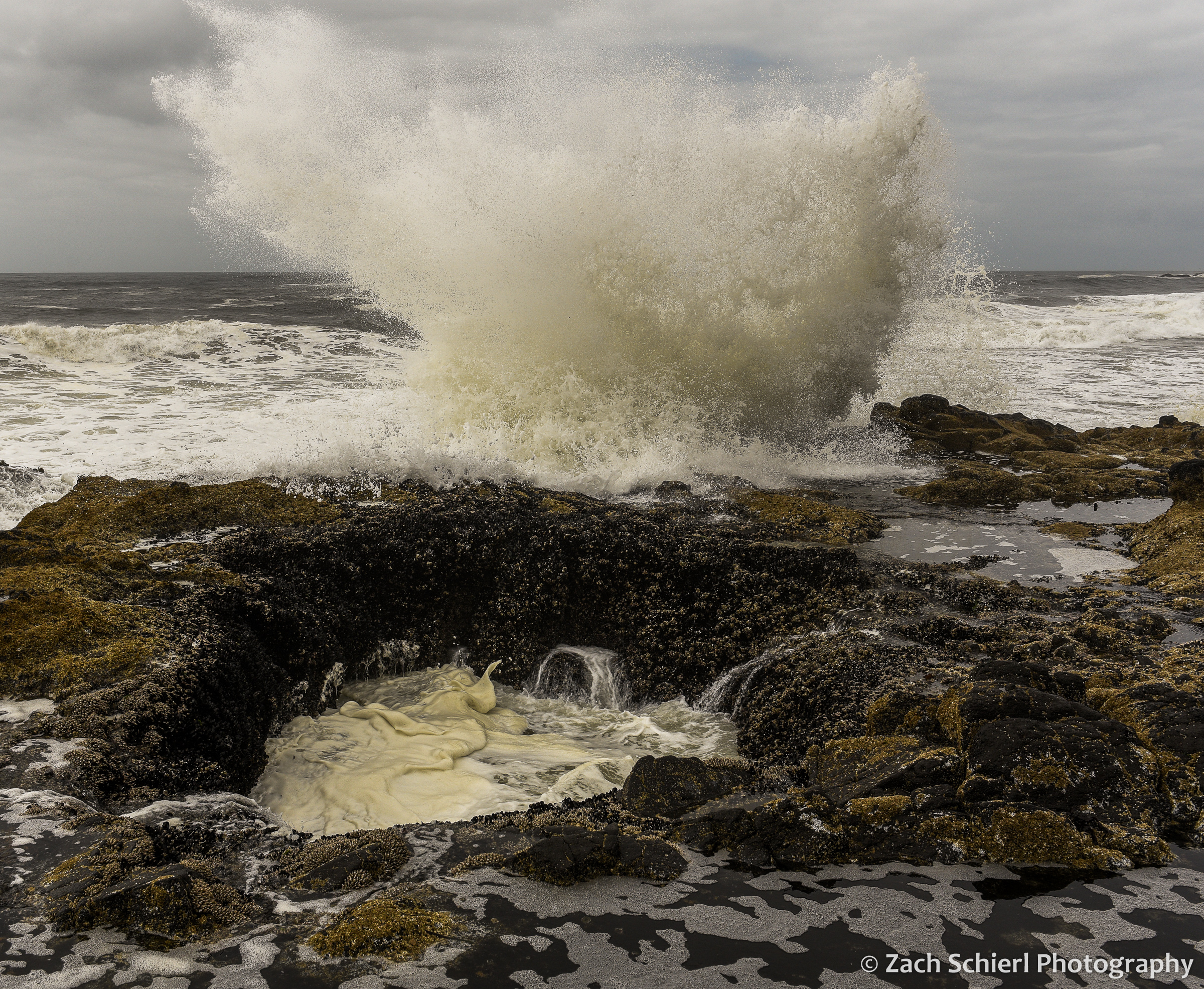

Thor’s Well is an interesting feature within the Cape Perpetua Scenic Area near Yachats. A ~10 foot wide hole in the rocky coastline, the Well connects to the open ocean via a small cave. The well alternately drains and fills as the waves roll in and out. Watching the water roll into the Well and waves crashing against the rocks was a mesmerizing experience.

Scattered bogs along the Oregon Coast host rare patches of Darlingtonia californica, the California Pitcher Plant. One of the few species of carnivorous plants native to the Pacific Northwest, the translucent patches on the leaves supposedly confuse insects trying to escape from inside the plants.

Darlingtonia californica

What at first glance appear to be rocks sticking up out of the water are actually the remains of a massive tree stump in Sunset Bay near North Bend. Large concentrations of dead trees, often partially buried in sand, are found all up and down the Oregon Coast, and are often referred to as “Ghost Forests”. Some of these trees, particularly the ones found in coastal estuaries, appear to have been killed by rapid subsidence associated with large earthquakes along the Cascadia Subduction Zone just offshore. Analysis and dating of these trees have revealed that large “megathrust” earthquakes are a regular occurrence in the Pacific Northwest. In the case of the trees seen here in Sunset Bay, it appears to be unclear if earthquakes or more run-of-the-mill processes (such as coastal erosion) are the culprit.

These tilted rocks at Shore Acres State Park near North Bend have appeared in many a geology textbook! Shore Acres is home to one of the world’s most striking examples of what geologists call an “angular unconformity,” where flat-lying sedimentary rocks (visible in upper left) rest directly on top of older, tilted sedimentary rocks. The boundary between the flat rocks and the tilted rocks represents a large chunk of geologic time missing from the rock record. Several hundred years ago, geologists recognized angular unconformities as some of the first strong evidence of the Earth’s immense age, as they require multiple cycles of sediment deposition, burial, uplift, and erosion in order to form.

Sea lions and seals hauled out on Shell Rock near Simpson Reef. Interpretive signs at this overlook proclaimed that this is the largest haul-out site for sea lions on the Oregon Coast.

Coastal sand dunes mirror the clouds at Myers Creek Beach south of Gold Beach, Oregon

Sunset at Arch Rock, between Brookings and Gold Beach, Oregon

A closer view of Arch Rock.

The first quarter moon hovers over sea stacks along the Oregon Coast south of Gold Beach, Oregon.

A late afternoon view of Lone Rock Beach and Twin Rocks from the Cape Ferrelo Viewpoint near Brookings, Oregon.

Wildflowers and Waterfalls of the Columbia River Gorge

Looking east along the Columbia River Gorge toward The Dalles on an alternately sunny & rainy March afternoon.

In the home stretch of its more than 1,000 mile-long journey from the Canadian Rockies to the Pacific Ocean, the Columbia River has carved a spectacular canyon that now forms the border between Oregon and Washington: the Columbia River Gorge. Nearly 100 miles in length, the Columbia River Gorge is one of the most unique landscapes in the Pacific Northwest, and home to some spectacular geology. Most of the gorge is carved into the Columbia River Basalts, layers upon layers of volcanic rock formed by vast lava flows that inundated most of central and eastern Washington about 16 million years ago. More recently, a series of large glacial outburst floods at the end of the last ice age broadened and re-shaped the gorge as they raged their way down the Columbia River to the Pacific Ocean, creating many of the landforms that we see today.

By the time the Columbia River enters the gorge, its elevation has already dropped to just 160 feet above sea level. The low elevation of the gorge makes it one of the warmest areas in the Pacific Northwest, and a prime destination for some early season camping. We recently spent three days in the Columbia River Gorge soaking up what passes for balmy weather this time of year around here.

An early spring view of the eastern Columbia River Gorge from Rowena Crest Overlook on the Oregon side of the gorge.

Motorcycle headlights illuminate the sweeping curves of the Historic Columbia River Highway just below Rowena Crest. The constellation of Canis Major sits just above the horizon. While the historic highway has been largely replaced by the much less charismatic I-84, large portions remain as backroads or hiking trails.

Two of the main attractions in the Columbia River Gorge are wildflowers and waterfalls. Even now, in mid-to-late March, the wildflower show was already in full swing, particularly in the drier, warmer, eastern reaches of the gorge:

Shooting stars (Dodecatheon sp.) are among the early blooming wildflowers in the eastern Columbia River Gorge. A yellow fritillary (Fritillaria pudica) lurks in the background.

Grass widows (Olsynium douglasii) are some of the earliest wildflowers to bloom in large numbers in the eastern Columbia River Gorge.

More grass widows…

Most grass widows are a vibrant pinkish purple color, but white petals are also found here and there.

Pungent desert parsley (Lomatium grayi) at Horsethief Butte.

One of the most remarkable sights in the Columbia River Gorge is experiencing the rapid change in environment as you drive through the gorge from east to west. The Dalles, located near the eastern end of the gorge, lies in the rain shadow of the Cascade Range and receives very little precipitation: just 14 inches annually. Here, the rocky slopes of the gorge are nearly devoid of any vegetation other than wildflowers and grasses. Just half an hour and a handful of freeway exists to the west, the average annual precipitation has increased to about 30 inches at Hood River, and ponderosa pine and Douglas fir cover the slopes. 20 more miles/minutes to the west, at Cascade Locks, annual precipitation rises to over 75 inches and the gorge is filled with the dense, shady, and mossy forests typically associated with the Pacific Northwest. In other words, you can travel from a true desert to a near-rainforest in less than an hour, while driving on a nearly flat interstate that hugs the shore of massive reservoirs created by dams along the lower Columbia River.

Large clusters of balsamroot (Balsamorhiza sp.) were beginning to flower in some of the drier, eastern parts of the Gorge, like these at Horsethief Butte.

An unknown species of fungus shares a decaying log with some moss. Scenes like this are common in the wetter, western half of the Columbia River Gorge.

The combination of dramatic terrain and copious precipitation at the western end of the Columbia River Gorge (particularly on the more mountainous Oregon side) combines to form some of the most spectacular waterfalls in the United States. As the aforementioned ice age floods flowed through the gorge on their way to the Pacific, they removed the lower ends of valleys belonging to the Columbia’s many tributary streams. Consequently, many of these tributaries enter the gorge several hundred feet above river level, terminating in spectacular plunges that carry their water into the Columbia River:

Latourell Falls plunges over a cliff of columnar basalt at the western end of the Columbia River Gorge, not far from Portland. This photo is a bit blurry; the trails to several of these waterfalls were busy, even on a somewhat chilly Tuesday in March, making it hard to set up a tripod for a steady shot.

Elowah Falls, Columbia River Gorge, Oregon. This shady alcove was heavily burned in the Eagle Creek Fire of 2017, but is already showing signs of re-growth.

Starvation Creek Falls, Columbia River Gorge, Oregon

Starvation Creek Falls, Columbia River Gorge, Oregon

Let’s be clear: with temperatures in the 40s and 50s and the nearly constant winds that blow through the gorge, it was no spring break in Florida, but after a long winter and with the Cascades still buried in snow for several more months, the greenery and signs of spring were a welcome sight. (Even though we did have our tent totally chewed up by an unknown animal…a first for us in many, many nights of camping throughout the west!)