Coyote Gulch in Pictures

Jacob Hamblin Arch and a series of deep alcoves cut into the Navajo Sandstone are the highlights of a trip through Coyote Gulch.

This past weekend we made our first foray into the interior of the Colorado Plateau since moving to Utah. Our destination was Coyote Gulch, a well-known tributary of the Escalante River that straddles the boundary of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument and Glen Canyon National Recereation Area. Below are some photos from the trip:

The hike begins with a nearly six mile slog through the desert along, and often in, Hurricane Wash. Toward the end it gets interesting, but mostly it looks like this. Nice, but nothing to write home about.

After about three miles of walking along Hurricane Wash, the trail leaves Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument and enters Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. It is here that things start to get more interesting.

Soon, cliffs of Navajo Sandstone begin to rise up along the wash and become progressively higher as you head downstream. Eventually a small stream appears in the canyon bottom, after passing through several short sections of dry narrows like this one.

Eventually, Hurricane Wash meets Coyote Gulch, which is perhaps best known for a series of enormous undercuts carved into the smooth and sheer walls of pink Navajo Sandstone.

This was the largest alcove we encountered and we were fortunate enough to be able to camp in its shadow. For most of the trip, the air was incredibly calm and still and standing inside these alcoves felt like being inside a great rotunda or cathedral.

The scale of the alcoves is truly incredible and difficult to grasp without being there. Note Michelle for scale in the lower left.

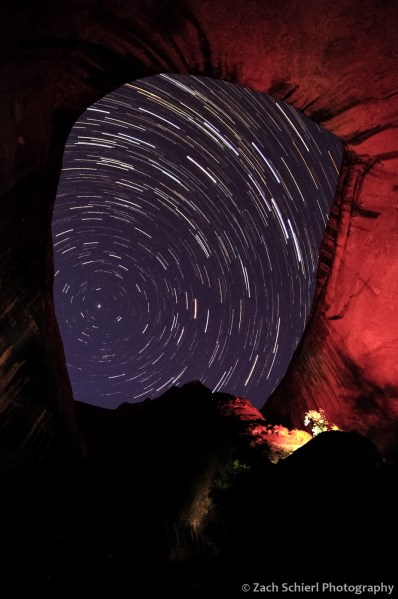

A group camped directly beneath the alcove on our first night spent several hours messing around with some extremely bright flashlights and spotlights. It was rather annoying when we were trying to fall asleep, but it actually made the star-trail sequence I was shooting come out rather nice.

Just a few hundred yards downstream from the large alcove where we camped was Jacob Hamblin Arch (also see photo at top of page). The creek makes a tight meander around the fin of rock containing the arch, allowing it to be seen from both sides.

On day two, we day-hiked from our campsite near Jacob Hamblin Arch down to the confluence of Coyote Gulch and the Escalante River, a distance of about 13 miles round trip. One of the many attractions en route was Coyote Natural Bridge.

It was mid-April and the canyon was incredibly lush and green. Many of the stream terraces alongside the creek were resplendent with green grasses and wildflowers.

Numerous springs emerge from the canyon walls along Coyote Gulch. Do you see the “T-Rex” in the upper left?

Moving downstream, Coyote Gulch leaves the Navajo Sandstone behind and carves into deeper and older layers of rock. Near the confluence with the Escalante River, the canyon walls are in the bright orange Wingate Sandstone.

Looking downstream along the Escalante River at its confluence with Coyote Gulch.

A ford of the waist-deep Escalante and a short walk upstream from the confluence reveals the impressive Stevens Arch high on the canyon wall.

Another view of Stevens Arch.

The surface elevation of Lake Powell when full is about 3,700 feet, almost exactly the elevation at the confluence of Coyote Gulch and the Escalante River, as shown by this Bureau of Reclamation benchmark.

At various times in Lake Powell’s history, most recently in the 1980s, the lake surface rose just high enough to flood the lowest reaches of Coyote Gulch and inundate the confluence under shallow water. The remnant water level lines are still faintly visible in lower Coyote Gulch.

The hike to the Escalante and back was a long one, but views like this around pretty much every bend made it seem shorter!

As a final note, Coyote Gulch has, for good reason, become an extremely popular destination over the years. We actually had some second thoughts about going after reading guidebooks that implored us not to visit on a holiday weekend in the spring (it was Easter) and after the BLM employee who issued our permit told us we would be “joining a party.” In the end, we found the over-crowding hype to be somewhat overblown. While there were more folks down there than you might expect to find in such a remote location, it could hardly be called a party. We camped in the most popular half-mile section of the gulch and couldn’t see anyone else from our site along the banks of the creek. We met just a handful of other groups on our hikes in and out of the gulch, and only occasionally encountered other people on our all-day hike down to the Escalante River and back. If you are seeking complete and total solitude or isolation, this is probably not the place for you. But we didn’t feel like the crowds detracted from the experience much if at all.

The increase in visitation to Coyote Gulch certainly creates challenges for the future. Hikers are now required to carry out all human waste, which seems to be a step in the right direction. However challenging keeping the gulch in pristine condition might be, I tend to believe that this situation is better, in the long-term at least, than the alternative. Coyote Gulch has been described as one of the last remaining echos of Glen Canyon, a small remnant of the scenic wonders that were submerged after the construction of Glen Canyon Dam and the filling of Lake Powell in the 1960s. Glen Canyon was lost ultimately because it was “the place no one knew.” The same cannot be said of Coyote Gulch. It is one of those places where the term “loved to death” gets thrown around, but ultimately we only fight to protect places that we love and value and it is hard to truly appreciate a place like Coyote Gulch solely through pictures. Hopefully the more people that go to Coyote Gulch and experience its majesty first-hand, the more people there will be to stand-up for it against future threats that are assuredly to come.

Colorful Geology at Valley of Fire State Park

Compaction bands in multi-colored Aztec Sandstone, just one of many geologic wonders in Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada

One of the great things about living in Southern Utah is the abundance of different climates within a small geographic area. When temperatures rise into the 90s and 100s in the low-elevation valleys, we can be in cool alpine meadows at 10,500′ in less than an hour. When snow, slush, and mud cover the trails in winter, vast portions of the Mojave and Great Basin Deserts are within a day’s drive. One of these desert areas is Valley of Fire State Park in southern Nevada, not far from I-15 between St. George and Las Vegas.

Perhaps not surprisingly, upon arrival at Valley of Fire one is greeted with an array of whimsically sculpted red rock formations. Now red rocks are hardly unique in this part of the country, and the crimson cliffs here are no more notable than those found anywhere else in Utah or Arizona. But head into the interior of the park and you soon realize the allure of the Valley of Fire. After cresting the red cliffs, the hues begin to multiply exponentially and before long you are surrounded by just about every color of sandstone imaginable.

A layer-cake of spectacular colors in Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada

To put it bluntly, the colors at Valley of Fire are simply ridiculous…and attributable to its unique geologic location. The rocks here are mostly equivalent to those found throughout southwestern Utah and the Colorado Plateau. The Aztec Sandstone, the dominant rock unit exposed in the park, is the equivalent of the Navajo Sandstone that makes up the cliffs of Zion National Park. Geologists just assign it a different name when it appears in Nevada and the Great Basin. Perhaps the distinct name is appropriate though, given that the sandstone seems to take on a life of its own here.

Valley of Fire State Park lies within the Basin and Range province, a vast region covering Nevada and portions of half a dozen other western states where the Earth’s crust is being slowly but violently stretched apart. As the writer John McPhee once noted, so much stretching has occurred here that 20 million years ago, Salt Lake City and Reno would have been more than 60 miles closer together. Faults are abundant in this land, and fluids associated with some of these faults have at various times leached iron compounds from the originally all-red sandstone, causing some layers to become bright white, and re-deposited them in other layers, leading to the wide variety of colors.

Some of the most impressive colors are found just to the west of the “Fire Wave” feature near the northern terminus of the park’s scenic drive:

Vibrant colors in the Aztec Sandstone in Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada

A feature known as the “Fire Wave,” Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada

While there are numerous hiking trails, there is also lots of off-trail terrain to explore. Some of the most spectacular scenery can be found by parking at one of the numerous pull offs and just wandering out into the rock wonderland. One particular geologic feature of note is what are known as “shear-enhanced compaction bands,” thin brittle fins of rock that rise almost vertically out of the ground and often run continuously for dozens to hundreds of yards. At first glance, these features look like mineral veins, but upon closer examination they are composed of the same material as the surrounding sandstone, but are obviously slightly harder than the host rock. In many places there are two perpendicular sets of the bands, forming a checkerboard like pattern superimposed on the sandstone.

Compaction bands in the Aztec Sandstone, Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada

The bands are the result not of stretching, but of compressional forces that predate the formation of the Basin and Range. Stresses associated with an earlier mountain building episode (known as the Sevier orogeny) created these funky bands by essentially “squeezing” together (and even breaking) the sand grains that make up the rock, eliminating much of the empty space between the grains and forming a miniature layer of tougher, harder, and more compact sandstone that is slightly more resistant to weathering and erosion. As a result, the bands tend to just out from the surrounding slickrock by several inches, and even several feet in some locations. For such a seemingly obscure feature, many papers have been written about these compaction bands (and similar ones in a few other locations in the region). However my understanding of the structural processes behind their formation is limited and the most recent articles about them appear to be behind a paywall. If anyone reading this has more insight into these things, I would love to hear from you.

As mentioned before, these bands are quite thin, in most less than a centimeter thick and thus, sadly, quite brittle. They are easily broken by an errant boot step so if you find yourself among them, tread carefully so that future visitors will be able to experience this unique and colorful landscape.

Sunset from the Old Arrowhead Road in Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada

The “Caves” of Cathedral Gorge State Park

The badlands of Cathedral Gorge State Park, Nevada

Next time you find yourself in extreme eastern Nevada with time to spare, I highly recommend checking out Cathedral Gorge State Park. This gem lies tucked away on the floor of Meadow Valley, about halfway between Las Vegas and Great Basin National Park, not far from the bustling hub of Panaca, Nevada. In other words, for a place fully accessible by paved roads, Cathedral Gorge is about as off-the-beaten path as you’re going to get.

Despite its under-the-radar status, Cathedral Gorge was established all the way back in 1935, and was one of Nevada’s four original state parks (along with the more well-known Valley of Fire north of Las Vegas). The highlight here is a shallow valley excavated out of a layer of soft lake sediments by Meadow Valley Wash and numerous small tributary streams. The sediment was originally deposited in a freshwater lake that called Meadow Valley home during wetter times in the Pliocene epoch (~2.5-5 million years ago). This area has been the epicenter for some pretty extensive volcanic activity over the past few dozen million years, so the sediment that accumulated in the lake was rich in volcanic ash.

Today, with the lake gone, the exposed sediment is so soft that it erodes extremely rapidly. Few plants can gain a foothold in earth that is crumbling so rapidly, so the water (and to a lesser extent, wind) have created a intricate landscape of badlands along the margin of the valley. The scenery is bizarre and not all that unlike what you might find in the famous badlands of South Dakota and the Great Plains. It definitely feels out of place in the sagebrush expanses of the Great Basin. While Cathedral Gorge bakes in the summertime, during our visit it was cold, windy, and virtually empty. We saw not another soul on a four mile loop hike around the perimeter of the valley.

Miller Point Overlook, Cathedral Gorge State Park, Nevada

The terminus of one of the narrow “mud slot canyons” in Cathedral Gorge State Park, Nevada

While the loop hike around the valley was enjoyable (if a bit windy), we didn’t stumble upon the highlight of our visit until we started poking around the rock formations adjacent to the trailhead parking lot. In a matter of minutes, we found ourselves exploring a landform that I still don’t have the right words to describe.

At the edge of the valley, runoff has carved a series of deep, extremely narrow, and almost perfectly vertical crevices into the soft sediments. The park calls them “caves” but the words cave, crevice, gully, crevasse, gorge, and ravine all fail to accurately capture their bizarre and truly unique nature. Perhaps the best way to describe them is as “slot canyons of mud.”

They evoke the sandstone slot canyons of Utah in the sense that they were so narrow that in many spots only a tiny sliver of blue sky could be seen overhead. Unlike most slot canyons though, whose delicate curves are clearly the result of flowing water, the walls here were angular and almost perfectly vertical. It was as if someone had carved huge blocks out of the mud with a chainsaw and then splattered the walks with mud to cover their tracks. Each little mud slot terminated abruptly in a roughly circular chamber whose walls were lined with linear grooves etched into the mud, extending all the way up to the rim. These chambers were clearly the work of waterfalls that spill into the canyons with each heavy rain.

As fragile and precarious as the mud walls looked, there were surprisingly few signs of catastrophic collapse. We explored about a half dozen of these little canyons, all of which were located right along the main road into the park. There were surely more that we missed, good enough reason to make the drive back to Meadow Valley another day.

Water flowing into the gullies erodes and redeposits mud, creating intricate shapes and patterns that line the walls.

Light streaming into a deep “mud slot canyon” in Cathedral Gorge State Park, Nevada