I’ve been an astronomy nut ever since my parents gave me a small reflecting telescope for my 10th birthday. I located Saturn, complete with its too-good-to-be-true rings, within 10 minutes of setting it up for the first time, although my parents refused to believe me until they had a look for themselves. I majored in astronomy, own a telescope that barely fits in my car, and come to think of it, every “real” job I’ve ever had has involved astronomy. NASA’s Astronomy Picture of the Day has been my homepage for longer than I can remember.

Given my disposition towards both astronomy and photography, it seems superfluous to say that I’ve always enjoyed astrophotography. Taking photographs of celestial objects presents a set of challenges not encountered by photographers who go home after the sun dips below the horizon, the majority of which revolve around the fact that most astronomical objects are rather dim, requiring long exposure times and extra equipment to capture.

Quite frequently I’ll get asked if I’ve ever seen any UFOs while gazing up at the sky. My standard response is that, while I’ve certainly seen a lot of weird *#&@ in the sky, I’ve yet to see anything that didn’t ultimately have a logical explanation, even if it took a little head-scratching to figure it out (high altitude weather balloons are the worst!).

A prime example of this occurred this past summer during a nighttime observing and photography session. I was attempting to get a 180 degree panorama of our home galaxy, the Milky Way, stretching across the summer night sky. I had my camera mounted on a tripod head that compensates for the rotation of the Earth, allowing me to take exposures several minutes in length while avoiding star trails in my images. It was dark and clear enough that I was able to get some good shots of the summer Milky Way and its complex and sinuous inky-black interstellar dust lanes, as well as some decent shots of some galaxies and nebulae through a telescope:

The Milky Way in the constellations of Scorpius and Sagittarius. This portion of the Milky Way is home to the nucleus of our galaxy, making the Milky Way appear brighter here than anywhere else in the sky.

The Milky Way in the constellations of Scorpius and Sagittarius. This portion of the Milky Way is home to the nucleus of our galaxy, making the Milky Way appear brighter here than anywhere else in the sky.

The Lagoon Nebula, also known as M8, a vast cloud of hydrogen gas giving birth to new stars. A “stellar nursery” as astronomers like to say.

The Lagoon Nebula, also known as M8, a vast cloud of hydrogen gas giving birth to new stars. A “stellar nursery” as astronomers like to say.

While my shots of the galactic center in the southern sky were turning out well, as I began to pan my camera around to the east and then finally north, I noticed that faint but noticeable bands of diffuse red and green light were creeping into my image.

My immediate thought was sensor noise. The CCD chip on my old DSLR (a Nikon D70) had a habit of heating up during repeated long-exposures. This thermal radiation from the sensor manifested itself as a bright purple/pink haze occupying one corner of the photo, making any attempt at serious astrophotography futile. Perhaps something similar was happening here. I quickly ruled this out for a number of reasons. Most importantly, the apparition was showing itself only in photos taken towards the north, meaning that the source couldn’t be the camera, but rather something in the sky itself. The colors ruled out high clouds, and it wasn’t in the proper direction to be the result of artificial light pollution. The closest city of any significant size to the northeast was several hundred miles away.

Whatever it was, neither myself or any of my observing companions could see it with the naked eye. A bit eerie perhaps, but not at all uncommon. Many astronomical phenomenon are too faint to see without long-exposure photographs. In fact, the first time I saw the aurora borealis, I captured it with my camera several hours before it became bright enough to see with the naked eye.

A auroral display was actually my second thought. What I was seeing in my photos definitely resembled one. Red and green are the colors produced by nitrogen and oxygen, the two primary components of our atmosphere, after being excited by collisions with magnetic particles brought to Earth by the solar wind. Most auroral displays consist of some combination of these two colors and what I was photographing appeared only in the northern sky which fit the theory to a tee. Furthermore, the Sun had been especially active in the week or so prior. It was perfect except for one slight problem: I was in Colorado.

Auroras in Colorado are definitely not unheard of….but not exactly common either. One thing was certain: if an aurora HAD crept this far south, then the northern portions of the country would simultaneously be getting the show of a lifetime. A quick check of spaceweather.com, the one stop shop for up-to-the minute aurora information, showed this was not the case. Strike two.

I actually didn’t figure this one out until many days later, when I inadvertently ran across an article about some Pacific Northwest photographers who had captured something called “airglow” in some photos of the Milky Way taken at Mt. Rainier around the same time. A momentary glance at their photos and I knew I had my answer.

Here’s the final panorama I produced. The airglow (red and green splotches at left) was changing rapidly enough that it caused major headaches trying to stitch the images together. Consequently I didn’t quite get my 180 degree panorama, there’s a bit missing on the northern end (lower left).

Airglow is exactly what it sounds like (a rare thing in science, I know…): glowing air. Incoming solar radiation and cosmic rays ionize oxygen and nitrogen atoms in our atmosphere during the day and then then these atoms regain their electrons at night, emitting light in the process. This is similar to what happens during an aurora, except that it’s happening ALL THE TIME. Airglow is always there, it’s just really, really faint; you need to be somewhere extremely dark to have a chance of seeing it, even with a camera. Even a miniscule amount of light pollution will render it invisible. It does tend to be brighter when solar activity is high, although it is not nearly as dependent on the solar cycle as its brighter cousin, the aurora.

So what began as an unidentified and undesirable annoyance in my photos (and when trying to stitch together my panorama, boy it sure was!) turned out to be a rarely captured celestial phenomenon I had never even heard of, much less one that I had intended on photographing that evening. Next time someone asks me about UFOs, I’ll just refer them to this page.

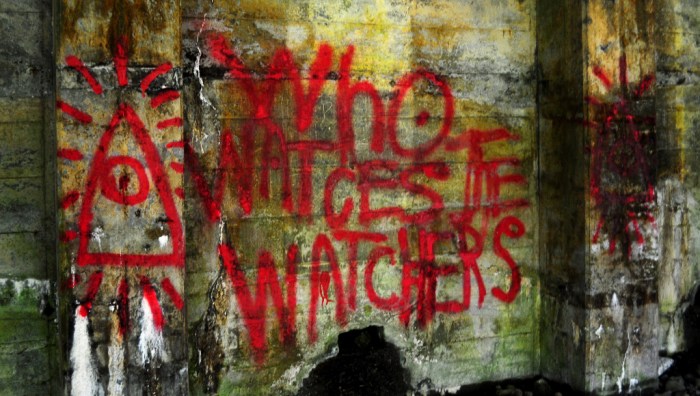

Walking through a large concrete snowshed along the Iron Goat Trail, built at the site of the 1910 Wellington disaster to prevent future avalanches from sweeping trains and passengers off the rails.

Walking through a large concrete snowshed along the Iron Goat Trail, built at the site of the 1910 Wellington disaster to prevent future avalanches from sweeping trains and passengers off the rails.

Deep snow and avalanches ultimately get the better of anything man builds to lessen their impact

Deep snow and avalanches ultimately get the better of anything man builds to lessen their impact