2024 GSA Calendars

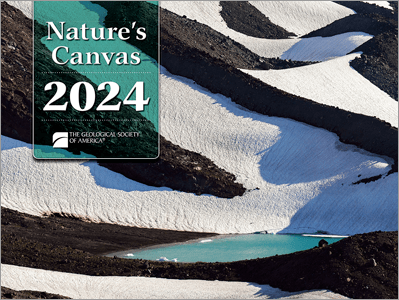

I’m excited to announce that one of my photos was chosen for the cover of the Geological Society of America’s annual calendar! The image is of a blue meltwater pool on the west slopes of Mt. Rainier that I took a few years back. Here’s what it looks like on the calendar:

I had a photo of Sunset Arch in Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument chosen for the inside of the calendar a few years back, but this is my first time on the cover. I received some sample copies of the calendar yesterday and the images are top-notch throughout.

You can order a copy of the calendar here for the low, low price of just $9.95! (It’s possible the price may be higher if you are not a member of GSA, I’m not positive…)

Merry Christmas and Happy New Year!

An Eclipse Expedition to Oregon

Every month, during new moon, the Moon passes between the Earth and the Sun. Unfortunately, due to the Moon’s tilted orbit, it usually passes just above or below the Sun, making those of us here on Earth oblivious to its passage. Twice a year though, the Moon passes through the plane of our orbit around the Sun during new moon, leading to a solar eclipse. Some of these eclipses are partial, where the Moon takes a bite out of the Sun, typically unbeknownst to those not monitoring the skies with eclipse glasses. More spectacular are the total eclipses, which occur when the Moon is close enough to us in its elliptical orbit that its disk is large enough to fully obscure the Sun, turning day briefly into dusk. A third option occurs when the Moon is farther away from us in its elliptical orbit. Even if the geometry is correct to produce a total eclipse, the Moon’s smaller size in this case means its not large enough to fully cover the Sun. This results in an annular eclipse, in which a ring (or “annulus”) of sunlight is visible around the dark circle of the new moon.

Partial eclipses are a dime a dozen, but given the small size of the Moon’s shadow relative to Earth, total and annular eclipses can only been seen from a narrow strip of land. Stand even a few meters outside that band, and you’ll see just a partial eclipse. I’ve seen probably half a dozen partial eclipses over the years, and in 2017, we made the eight hour drive from southern Utah to Riverton, WY to see a total solar eclipse. (The drive ended up being twice as long on the return, due to “eclipse traffic.”) That experience was spectacular, and immediately led to conversations about when we could see another.

While annular eclipses don’t provide quite the all-encompassing sensory experience of a total eclipse, I was nevertheless excited to complete my own personal “eclipse trifecta” by travelling to Oregon last weekend for the October 14, 2023 annular eclipse. The last annular eclipse visible from the United States was over a decade ago, on May 20, 2012, when the path of annularity swept across the American Southwest. That date just happened to correspond with my undergraduate commencement ceremony, which was sadly not in the path of annularity. This prompted me to inquire with school officials about whether attendance was required to receive my degree. I was told it was, and thus that eclipse expedition ended before it began.

The 10/14/23 eclipse had been circled on my calendar for a long time, especially since we moved to Washington in 2019 and would be just a few hours north of the path of annularity. I had grand plans of leading a field trip for my students, but a national shortage of 12-passenger vans thwarted that idea months ago. Instead, on the evening of October 13th, my wife and I made the 4.5 hour drive from central Washington to La Pine State Park in Oregon, just inside the annular eclipse track. The weather forecast had been looking poor for the past week, and the last hour of the drive was through a steady rain. However, forecasts for the eclipse morning had slightly improved over the past 24 hours, and it seemed there would be at least a chance for some clearing around eclipse time. The campground was full, which I’m guessing was out of the ordinary for a wet, cold, weekend in mid-October.

The morning of the eclipse dawned cold and mostly cloudy, though there were patches of blue sky visible here and there. We decided to head southeast, away from the Cascades, to improve our chances of clear skies. After about an hour of driving, through intermittent patches of eclipse traffic, we arrived on the rim of “Hole-in-the-Ground,” a ~1 mile wide volcanic crater known as a marr, formed when magma encountered shallow groundwater about 15,000 years ago, resulting in a large explosion. Several dozen other groups were camped out on the rim of the hole in the hopes of seeing the eclipse. We pulled off into the sage with about half an hour to go until the start of the annular eclipse. The skies looked grim, with the patches of blue from an hour earlier having given way to a nearly uniform layer of gray mid-level clouds. We briefly debated weather to high-tail it east toward an area of sunlight on the horizon an unknown distance away, but eventually decided we probably wouldn’t make it in time.

This turned out to be the right call. About 15 minutes before annularity began, a hole in the clouds began to materialize and we caught our first glimpse of the partially eclipsed Sun:

With the Sun nearly 90% eclipsed at this point, the light began to take on a noticeably unnatural tone, much as it did in the final minutes before the total eclipse in 2017. The gap in the clouds became steadily larger, as did our excitement at the prospect we might actually see the celestial alignment we had come for. At 9:20 am, annularity began, right on schedule, as the Sun peered down through the only sizeable break in the clouds for miles around. Joyous shouts of excitement echoed across the hole as other parties spotted the hole-in-the-sun through the hole-in the-clouds from the hole-in the-ground. What cosmic symmetry!

The extra hour of driving had bought us an additional minute or so of annularity, for a total of just under four minutes. That time flew by. By the time we looked through the telescope a few times and snapped a few pics, the annular eclipse was over. The clouds sealed back up again about 10 minutes after annularity ended.

Having seen what we came to see, it was now 10:00 am on a beautiful (if you’re not trying to see an eclipse) and pleasant weekend in central Oregon. We spent the rest of the weekend going on some short hikes and enjoying some great food in Bend before returning home.

Exploring Northern New Mexico

Despite having grown up just a few hours away in northern Arizona (and having lived in the other two ‘Four Corners’ states: Colorado and Utah), I’ve spent very little time in New Mexico. This summer, my wife and I had the chance to spend about a week in northern New Mexico as part of a larger road trip to the southwest, checking out Santa Fe and some of the national monuments in the area.

Our first stop was a place I’ve wanted to visit for a long time: Chaco Canyon. The epicenter of Ancestral Puebloan culture, this broad and shallow canyon is only accessible via many miles of dirt roads, which probably explains why we saw relatively few people once we were there! We arrived mid-afternoon and spent the night at the park campground before exploring several of the Chacoan “great houses” on self-guided trails early the following morning to beat the heat.

After proceeding south to visit friends in Santa Fe for several days, we headed into the Jemez Mountains north of town. Atop the Jemez Mountains sits Valles Caldera, a ~13 mile-wide depression created by an explosive volcanic eruption about 1.25 million years ago. The caldera and surrounding landscape are today part of Valles Caldera National Preserve (similar to a national park, except with hunting allowed), which was established in 2000 when a 95,000 acre private ranch was sold to the federal government. The southern portion of the caldera is occupied by a vast and stunningly beautiful grassy meadow known as Valles Grande. Several small lava domes punctuate the meadow, remnants of volcanic gurgles that occurred after caldera formation. We enjoyed a ranger-led hike around one of them, Cerro La Jara, and learned about the geological and human history of the region, as well as the local wildlife. We saw many prairie dogs, as well as a pair of coyotes meandering around the meadow stalking a massive herd of cow elk.

The eruption that created Valles Caldera deposited a thick layer of volcanic ash and tuff across the region known as the Bandelier Tuff. At the foot of the Jemez Mountains is Bandelier National Monument, our final stop in New Mexico, where Ancestral Puebloans carved dwellings into and out of this relatively soft and workable rock along what is now known as Frijoles Canyon:

The national parks of southern New Mexico and western Texas (White Sands, Carlsbad Caverns, Guadalupe Mountains, Big Bend) are some of the few in the west I’ve yet to visit, so a return to the “Land of Enchantment” will be needed soon!